| I had the opportunity to spend the afternoon with the co-founders of Accelyst Technologies INC., a company founded at McMaster University in 2010 and is still going strong as a “small to medium” start-up company. The company runs out of office space rented from McMaster Innovation Park. I chatted with Dr. Henry Ko and Dr. Adam Kinsman, both computer engineers, about their struggles and successes as entrepreneurs; I also asked them about the lessons they learned about innovation, creativity and entrepreneurialism in the twenty-first century. Ko and Kinsman first explained to me the various benefits and services offered by MIP: besides providing reasonable rent for office space, MIP also encourages networking, collaboration and cross-pollination between various start-ups. Essentially, MIP is an incubator for innovation. But MIP is more than a “think-tank” for ideation and dreaming; MIP also houses the “infrastructure of innovation”—that is, funding and grant application support, patenting guidance, legal advice and accounting services—as well as guidance and mentoring opportunities. Many ambitious innovators think only about their ideas, not what problem their idea can solve; they also frequently forget about other essential ingredients like funding, patents, legal management. |

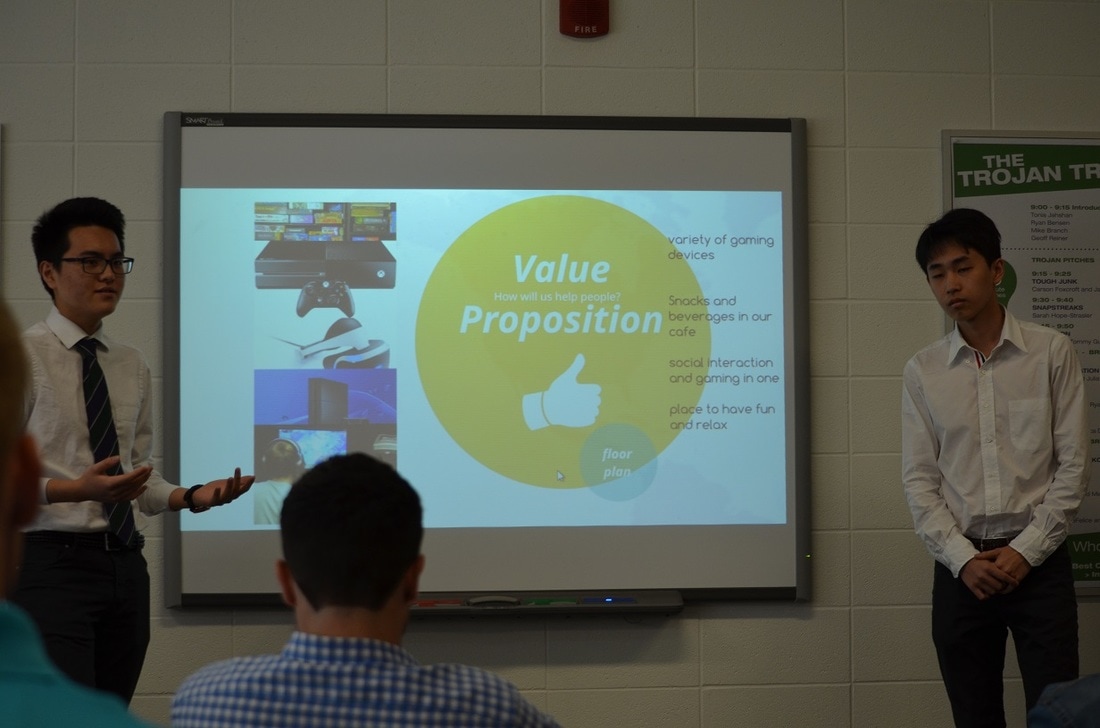

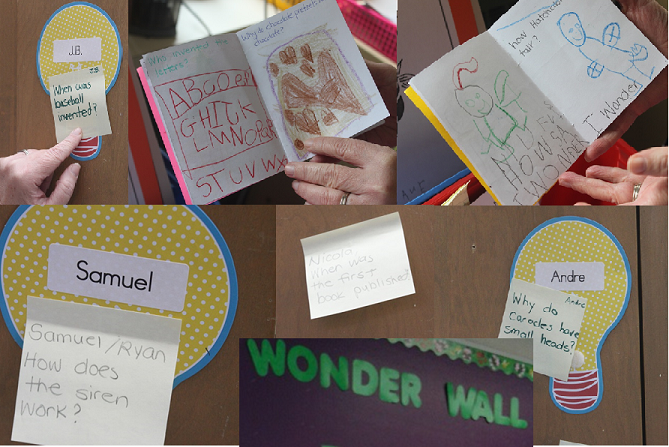

The first answer they proposed was simply this: “bad ideas aren’t dampened soon enough.” Too many companies spend too much time on unchecked and untested ideas, ideas that turn out to be bad ones. Ko and Kinsman urge innovators to kill bad ideas as soon as possible, so that good ones have time to germinate and flourish. This requires market testing, honest reflection and regular feedback.

The evaluation of ideas is fundamental to innovation. Testing products and prototypes (although expensive and difficult) are crucial to sussing out goods ideas from the bad ones. Innovators need to ask themselves if their idea is better than an incumbent; who is their target audience? Who can and will pay for the service or product?

Notice the reason for failure wasn’t perseverance; in fact, persevering with a bad idea often signals the death knell of an aspiring entrepreneur. The real goal is to persevere researching, reflecting and rejecting until the innovator finds a truly good idea.

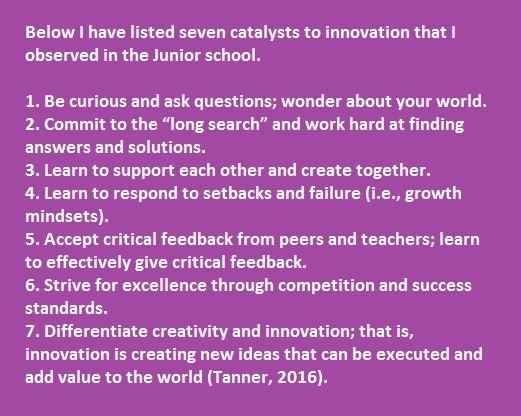

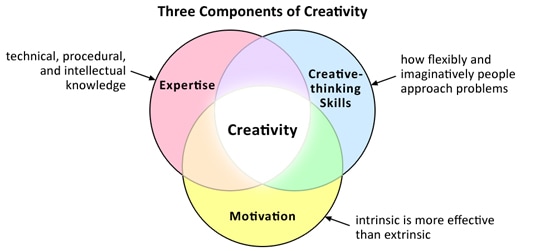

Fundamental knowledge is also key. Kinsman and Ko referenced physicist Albert Einstein, who didn’t throw out or ignore Newtonian mechanics but rather enveloped them. Both Ko and Kinsman urged educators to still teach the basics while also encouraging students to challenge foundations and develop links between competing systems. They also noted the need for growth mindsets.

This is what Dyer, Gregersen and Christensen (2011) say are the fundamental skills of an innovator: associating, questioning, observing, networking and experimenting. The reason Ko and Kinsman have been able to thrive as a start-up company is because they clearly have the DNA of innovators.

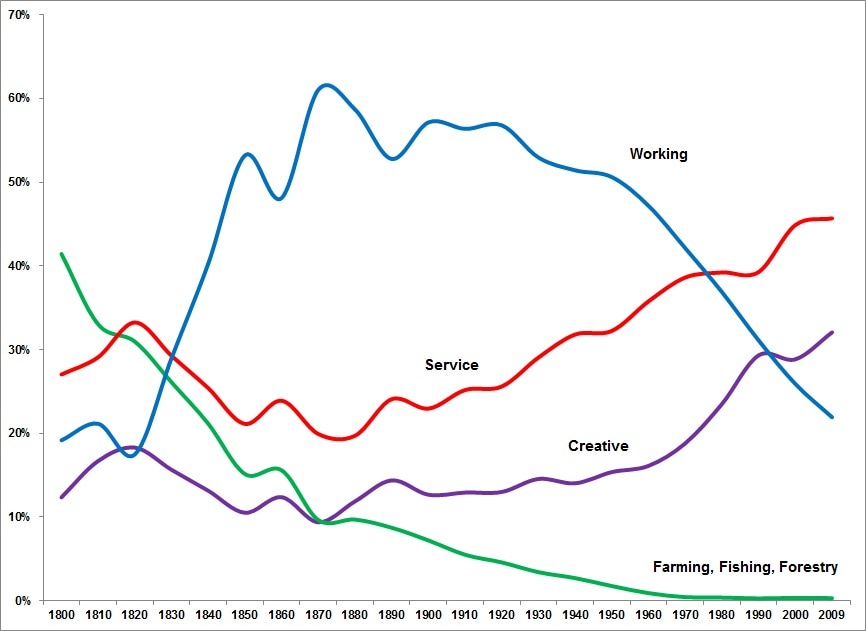

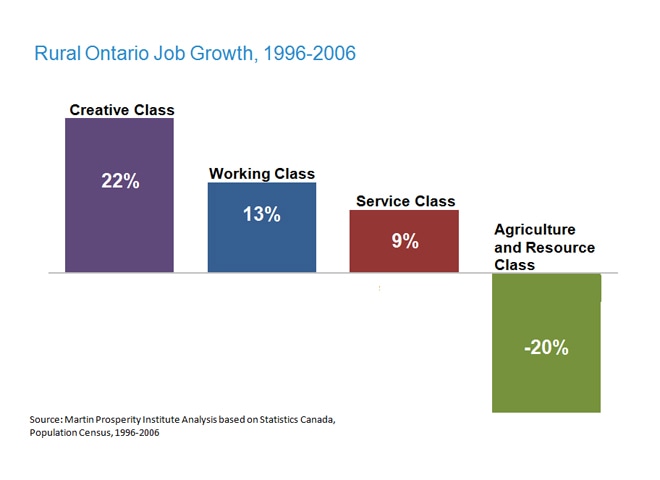

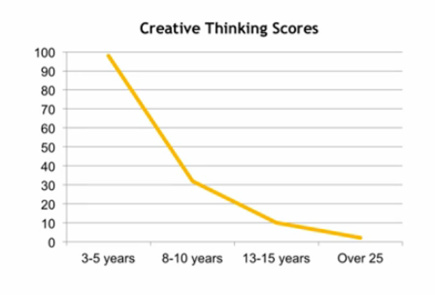

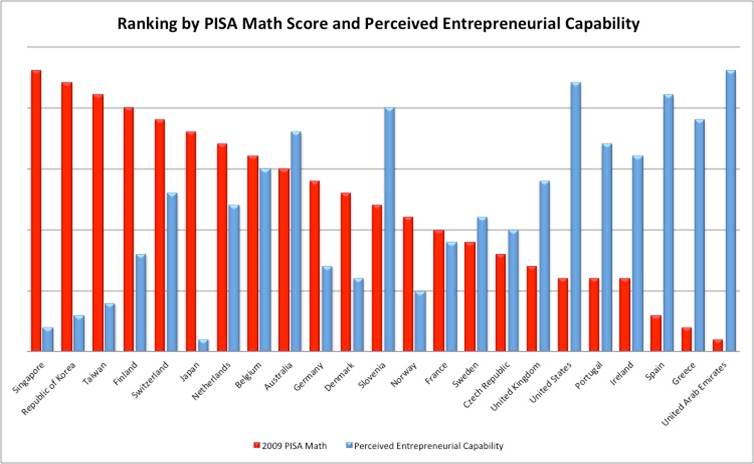

As educators preparing students for the twenty-first century, we clearly have a lot of work to do; we not only need to continue teaching the fundamental knowledge and skills, but we also need to foster growth mindsets, skills of innovators and nurture entrepreneurial spirits.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed