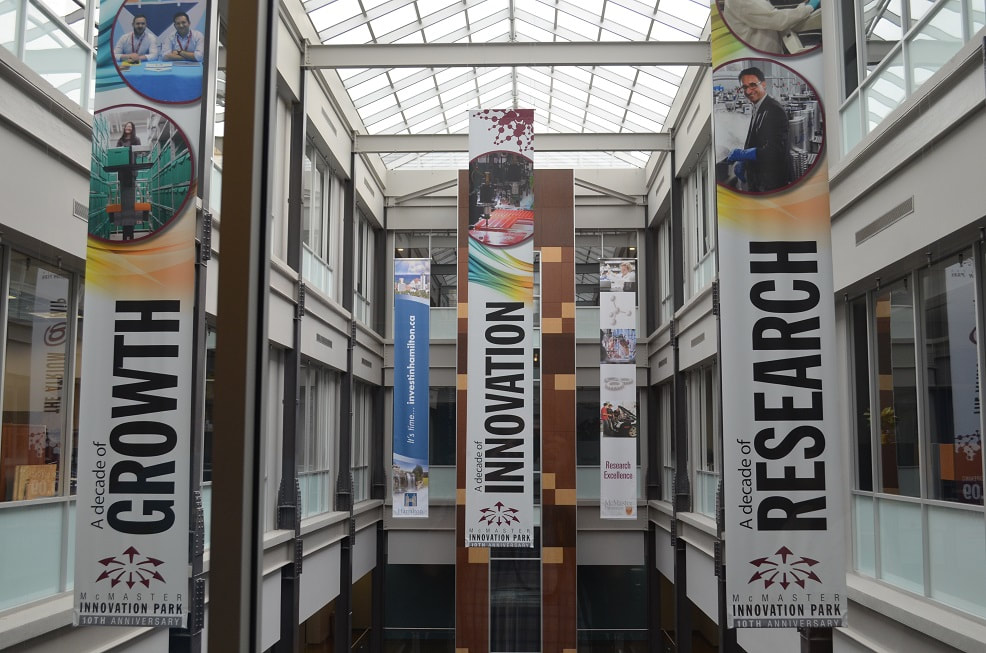

Early in July of this year (2017), I took the opportunity to do some field research for my Master’s degree project and for my sabbatical. I have been exploring the topic of innovation and entrepreneurialism in the educational context, but the ultimate goal is to prepare students for the competitive context of business in the real world. This brought me to McMaster Innovation Park (MIP) in Hamilton Ontario. Under the auspices of McMaster University, this sprawling campus includes automotive research facilities and a metals and materials research facility. My purpose was to visit the “The Atrium,” which is “home to over 40 businesses and organizations that are fostering innovation through development of new businesses, products, and research initiatives with a focus on commercialization” (MIP, 2017).

| I had the opportunity to spend the afternoon with the co-founders of Accelyst Technologies INC., a company founded at McMaster University in 2010 and is still going strong as a “small to medium” start-up company. The company runs out of office space rented from McMaster Innovation Park. I chatted with Dr. Henry Ko and Dr. Adam Kinsman, both computer engineers, about their struggles and successes as entrepreneurs; I also asked them about the lessons they learned about innovation, creativity and entrepreneurialism in the twenty-first century. Ko and Kinsman first explained to me the various benefits and services offered by MIP: besides providing reasonable rent for office space, MIP also encourages networking, collaboration and cross-pollination between various start-ups. Essentially, MIP is an incubator for innovation. But MIP is more than a “think-tank” for ideation and dreaming; MIP also houses the “infrastructure of innovation”—that is, funding and grant application support, patenting guidance, legal advice and accounting services—as well as guidance and mentoring opportunities. Many ambitious innovators think only about their ideas, not what problem their idea can solve; they also frequently forget about other essential ingredients like funding, patents, legal management. |

Ko and Kinsman both estimated that most start-ups fail in the first two years of operation. As mathematicians, they avoid generalisations—so when Dr. Kinsman told me that only 5% of start-ups last beyond the first two years, I knew this number wasn’t dropped for hyperbolic effect. This means that an astonishing nineteen out of twenty companies are unsuccessful. They have witnessed the demise of countless companies at MIP. My question to them was why?

The first answer they proposed was simply this: “bad ideas aren’t dampened soon enough.” Too many companies spend too much time on unchecked and untested ideas, ideas that turn out to be bad ones. Ko and Kinsman urge innovators to kill bad ideas as soon as possible, so that good ones have time to germinate and flourish. This requires market testing, honest reflection and regular feedback.

The evaluation of ideas is fundamental to innovation. Testing products and prototypes (although expensive and difficult) are crucial to sussing out goods ideas from the bad ones. Innovators need to ask themselves if their idea is better than an incumbent; who is their target audience? Who can and will pay for the service or product?

Notice the reason for failure wasn’t perseverance; in fact, persevering with a bad idea often signals the death knell of an aspiring entrepreneur. The real goal is to persevere researching, reflecting and rejecting until the innovator finds a truly good idea.

The first answer they proposed was simply this: “bad ideas aren’t dampened soon enough.” Too many companies spend too much time on unchecked and untested ideas, ideas that turn out to be bad ones. Ko and Kinsman urge innovators to kill bad ideas as soon as possible, so that good ones have time to germinate and flourish. This requires market testing, honest reflection and regular feedback.

The evaluation of ideas is fundamental to innovation. Testing products and prototypes (although expensive and difficult) are crucial to sussing out goods ideas from the bad ones. Innovators need to ask themselves if their idea is better than an incumbent; who is their target audience? Who can and will pay for the service or product?

Notice the reason for failure wasn’t perseverance; in fact, persevering with a bad idea often signals the death knell of an aspiring entrepreneur. The real goal is to persevere researching, reflecting and rejecting until the innovator finds a truly good idea.

When discussing “risk taking,” both Ko and Kinsman qualified risk with education, research and analysis. As entrepreneurs, they take “calculated and informed risks” and only risks they can afford to lose if it comes to that.

Fundamental knowledge is also key. Kinsman and Ko referenced physicist Albert Einstein, who didn’t throw out or ignore Newtonian mechanics but rather enveloped them. Both Ko and Kinsman urged educators to still teach the basics while also encouraging students to challenge foundations and develop links between competing systems. They also noted the need for growth mindsets.

This is what Dyer, Gregersen and Christensen (2011) say are the fundamental skills of an innovator: associating, questioning, observing, networking and experimenting. The reason Ko and Kinsman have been able to thrive as a start-up company is because they clearly have the DNA of innovators.

As educators preparing students for the twenty-first century, we clearly have a lot of work to do; we not only need to continue teaching the fundamental knowledge and skills, but we also need to foster growth mindsets, skills of innovators and nurture entrepreneurial spirits.

Fundamental knowledge is also key. Kinsman and Ko referenced physicist Albert Einstein, who didn’t throw out or ignore Newtonian mechanics but rather enveloped them. Both Ko and Kinsman urged educators to still teach the basics while also encouraging students to challenge foundations and develop links between competing systems. They also noted the need for growth mindsets.

This is what Dyer, Gregersen and Christensen (2011) say are the fundamental skills of an innovator: associating, questioning, observing, networking and experimenting. The reason Ko and Kinsman have been able to thrive as a start-up company is because they clearly have the DNA of innovators.

As educators preparing students for the twenty-first century, we clearly have a lot of work to do; we not only need to continue teaching the fundamental knowledge and skills, but we also need to foster growth mindsets, skills of innovators and nurture entrepreneurial spirits.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed