According to Tony Wagner in his book The global achievement gap: why even our best schools don't teach the new survival skills our children need—and what we can do about it (2008), students need to learn “initiative and entrepreneurialism” (among other skills) to not only thrive but also survive in the changing social and economic global context of the 21st century. Entrepreneurialism is more readily associated with disciplines like business and technology courses; but in truth, the entrepreneurial spirit can be (and must be) nurtured in all disciplines. The essential catalyst to developing an entrepreneurial spirit is creativity and innovation. Researchers Saavedra and Opfer (2012) argue that similar to “intelligence and learning capacity, creativity is not a fixed characteristic that people either have or do not have. Rather, it is incremental, such that students can learn to be more creative” (p. 12). I agree that creativity and innovation must be taught, cultivated, and encouraged in all of our classrooms.

Sir Ken Robinson famously spoke at TED about the ways in which traditional “industrial age” approach to schooling actually kills creativity. If educators can kills creativity, then how do we nurture it?

Sir Ken Robinson famously spoke at TED about the ways in which traditional “industrial age” approach to schooling actually kills creativity. If educators can kills creativity, then how do we nurture it?

Can students be taught creativity?

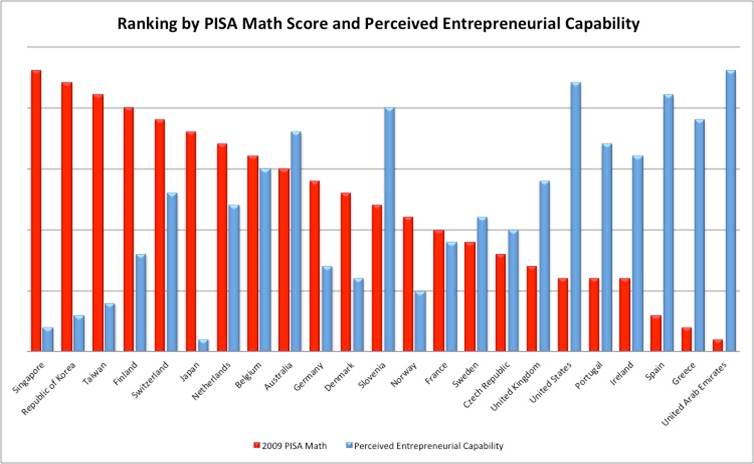

Dr. Yong Zhou notes in his book, World Class Learners, that 21st century students need to differentiate themselves within the context of “global homogenization” (2010, p.43). “For those in developed countries to be globally competitive, they must offer something qualitatively different” (Zhou, 2010, p.43). That differentiation is creativity, innovation and design thinking; “for businesses, it’s no longer enough to create a product that’s reasonably priced and adequately functional. It must be beautiful, unique, and meaningful” (Pink, 2005, p.33). Zhou compares Chinese education (which consistently ranks among the top in the work on standardised test in math and science; cp. PISA scores OECD), yet China is among the lowest nations on earth for developing patents (Zhou, 2010, p.128). According to the Global Entrepreneurial Monitor (GEM), “the quality of entrepreneurship in China is still unsatisfactory” and “the economic and social value of entrepreneurial activities needs to be improved” (GEM, 2014). On the other hand, Zhou points out, the United States (which consistent underperforms on standardized tests, is incredibly entrepreneurial and creative (Zhou, 2010, p.134). The United States has a “consistently high level of participation in entrepreneurship supported by favourable environmental conditions” (GEM, 2014). One key factor in China’s poor innovation and entrepreneurialism is a “test-writing culture” (Zhou, 2010, p.119); whereas, the United States has a culture and education system that fosters innovation (Zhou, 2010, p.93). Creating an environment rich in opportunities is what fosters creativity (cp. Gladwell, 2008, p.31; Coyle, 2009, p.62).

The chart below illustrates a fascinating correlation between successes on standardized tests (math) and perceived entrepreneurial capability (NB: China is not listed on this chart).

Dr. Yong Zhou notes in his book, World Class Learners, that 21st century students need to differentiate themselves within the context of “global homogenization” (2010, p.43). “For those in developed countries to be globally competitive, they must offer something qualitatively different” (Zhou, 2010, p.43). That differentiation is creativity, innovation and design thinking; “for businesses, it’s no longer enough to create a product that’s reasonably priced and adequately functional. It must be beautiful, unique, and meaningful” (Pink, 2005, p.33). Zhou compares Chinese education (which consistently ranks among the top in the work on standardised test in math and science; cp. PISA scores OECD), yet China is among the lowest nations on earth for developing patents (Zhou, 2010, p.128). According to the Global Entrepreneurial Monitor (GEM), “the quality of entrepreneurship in China is still unsatisfactory” and “the economic and social value of entrepreneurial activities needs to be improved” (GEM, 2014). On the other hand, Zhou points out, the United States (which consistent underperforms on standardized tests, is incredibly entrepreneurial and creative (Zhou, 2010, p.134). The United States has a “consistently high level of participation in entrepreneurship supported by favourable environmental conditions” (GEM, 2014). One key factor in China’s poor innovation and entrepreneurialism is a “test-writing culture” (Zhou, 2010, p.119); whereas, the United States has a culture and education system that fosters innovation (Zhou, 2010, p.93). Creating an environment rich in opportunities is what fosters creativity (cp. Gladwell, 2008, p.31; Coyle, 2009, p.62).

The chart below illustrates a fascinating correlation between successes on standardized tests (math) and perceived entrepreneurial capability (NB: China is not listed on this chart).

How do we teach creativity?

If ever there was an area in need of bridging theory and practice, then creativity theory is top of the list. When thinking of creative people, we often recall “outliers” like Shakespeare, Picasso, Disney, Bach, Austen, Gates, Jobs, The Beatles, and so on. Examining their lives seems to give us varied and circuitous paths to creative genius. Some might say that creativity is in our DNA or it isn’t (Wagner, 2012, p.23).

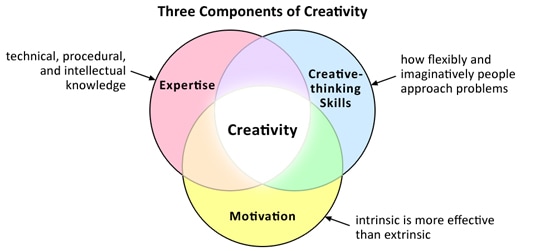

Teresa Amabile, Harvard Business Professor, wrote a seminal essay entitled “How to Kill Creativity” (1998). In her essay, she shows how current practices in business and education stifle creativity; but she also suggests ways to foster creativity as well.

See her Venn diagram below.

If ever there was an area in need of bridging theory and practice, then creativity theory is top of the list. When thinking of creative people, we often recall “outliers” like Shakespeare, Picasso, Disney, Bach, Austen, Gates, Jobs, The Beatles, and so on. Examining their lives seems to give us varied and circuitous paths to creative genius. Some might say that creativity is in our DNA or it isn’t (Wagner, 2012, p.23).

Teresa Amabile, Harvard Business Professor, wrote a seminal essay entitled “How to Kill Creativity” (1998). In her essay, she shows how current practices in business and education stifle creativity; but she also suggests ways to foster creativity as well.

See her Venn diagram below.

Creativity and innovation is an area of pedagogy that is linked to constructivist and connectivist learning theory. How do we create an environment that fosters risk-taking, ownership, and exploration? I am hoping to investigate this further in the coming months!

Cited Resources

Cited Resources

- Amabile, T. (1998). How to Kill Creativity. Havard Business Review. Retrieved June 08, 2016, from https://hbr.org/1998/09/how-to-kill-creativity

- Coyle, D. (2009). The Talent Code. New York: Bantam. Print.

- GEM Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. (n.d.). Retrieved June 08, 2016, from http://www.gemconsortium.org/country-profile/122

- Gladwell, M. (2008). Outliers. New York: Little, Brown and Co.. Print.

- Pink, D. (2005). A Whole New Mind. New York: Riverhead Books. Print.

- Saavedra, A. R., & Opfer, V. D. (2012). Learning 21st-century skills requires 21st-century teaching. Phi Delta Kappan, 94(2), 8-13.

- Wagner, T. (2012). Creating Innovators. New York: Scribner. Print.

- —— (2008). The Global Achievement Gap: Why Even Our Best Schools Don't Teach the New Survival Skills Our Children Need--and What We Can Do about It. New York: Basic. Print.

- Zhao, Y. (2012). World class learners: Educating creative and entrepreneurial students. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. Print.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed