There is, however, a problem with the mandate of preparing students for the future: the future is unknown. What future are we preparing students for? Parents and teachers are tempted to prepare students for the sort of future they faced. This isn’t always a bad thing, unless, of course, we are at a watershed moment in history. I am convinced we are at a watershed moment in the history of education, economics, history and civilisation itself. The future is going to be decidedly different place than the future of our parents or grandparents.

A point of clarification about “crystal-balling” the future… It always concerns me when educational pundits predict the future; too often the “unknown future” becomes a leveraging tool for fear-mongering and manipulation… and sometimes for speaking gigs, book deals and consulting fees. The professional development poster cries out “Beware of the future [insert problem]; this can only be solved by reading my book, coming to my lecture, attending my workshops”… The “unknown” is always a root cause of fear, and fear tends to cause hasty decision-making and short-sighted reactions. Since the future hasn’t actually happened yet, it is essentially “nothing.” As Shakespeare put it, we have a tendency to “make much ado about nothing.” We should base current decisions on the unknown “nothing” of the future.

Nevertheless, some of the ways we can “project” into the future is to look at current practices and values, compare the present to past epochs of human activity and to look at trends.

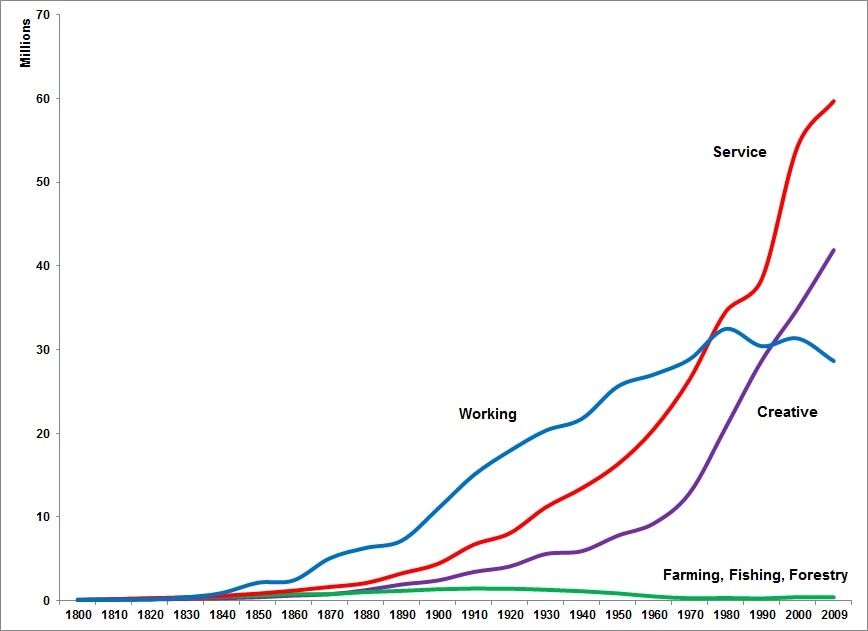

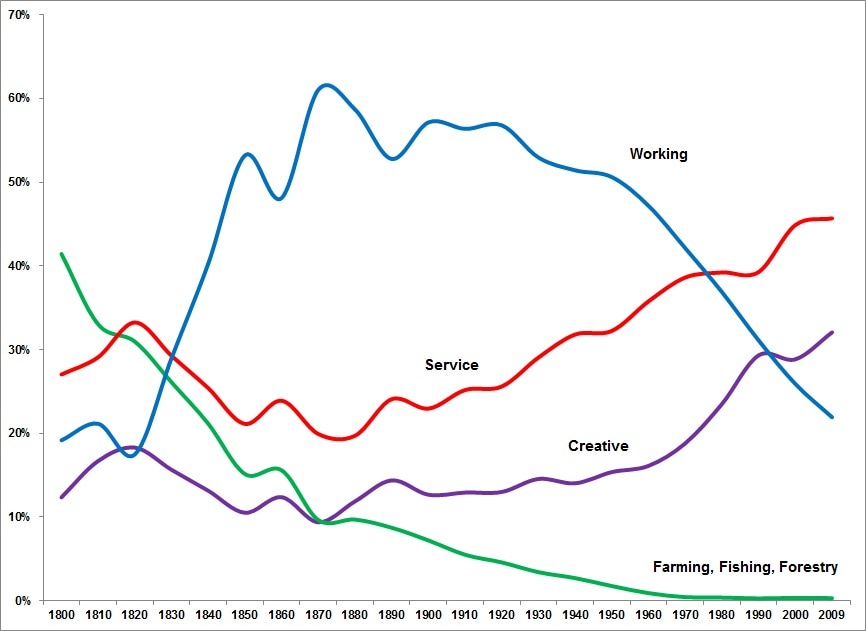

| In this blog post, I want to discuss the third “probability indicator” of the future… current trends and patterns. Richard Florida, in his book The Rise of the Creative Class, examines workforce trends in the United States. The graph below shows “Americans’ employment from 1800 to 2010, across the nation’s three great economic eras — the Agricultural Age running from the time of Western settlement until the early to mid-nineteenth century, the Industrial Age from the middle of the nineteenth century until the middle of the twentieth, and the new Creative Age, from the mid-twentieth century to the present” (Florida, 2012). |

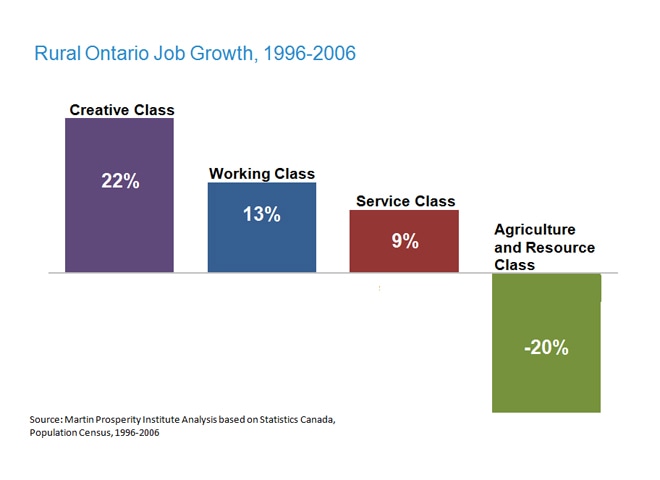

Similar trends are emerging in Canada as well; below is a graph showing job growth in rural Ontario.

Florida argues that we must invest in “the creativity of every single citizen and human being—in order to upgrade and generate new higher-paying jobs, address the gross inequities in our economy and society, and lay the institutional foundations for a new era of shared prosperity” (Florida, 2012).

In the minds of parents and teachers, “creative” pursuits are often equated with a diet of dessert. This is most evident in the realm of the arts (e.g., music, drama, painting, creative writing); desserts are nice to have but they are not necessary. As we look at the trends above, we see that creativity is no longer an optional “dessert” but rather a hardy and nutritious meal. We need to move creativity from the periphery of teaching and learning (i.e., “dessert”) to the heart of education (i.e., “dinner”).

Reference

Florida, R. (2012). "Creativity is the New Economy" The Huffington Post. Retrieved 2 May, 2017, from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/richard-florida/creativity-is-the-new-eco_b_1608363.html

RSS Feed

RSS Feed