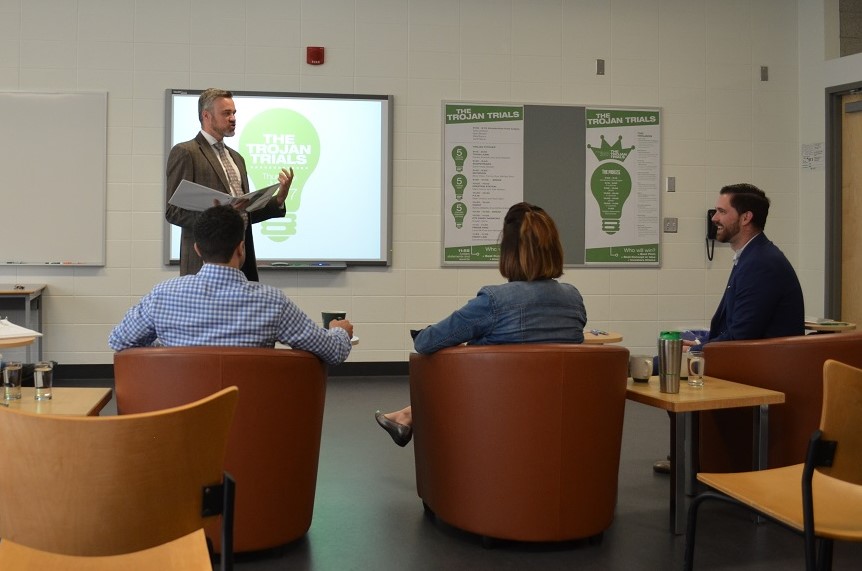

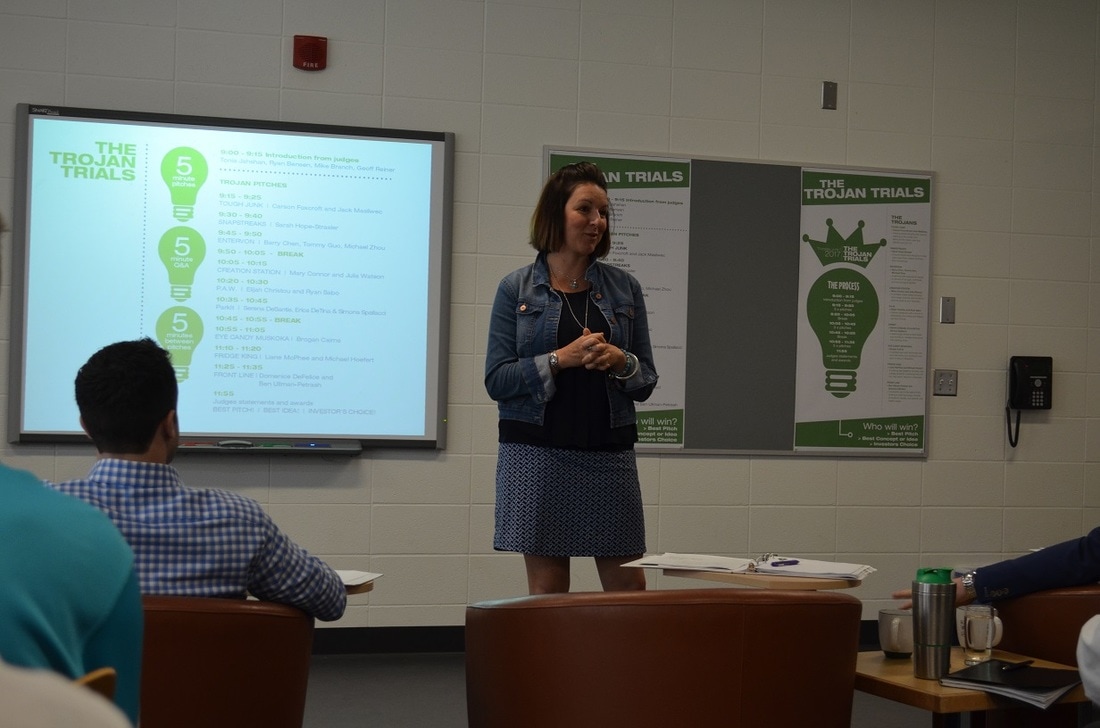

In the Senior school, students have the option of taking a Small Business course focusing on entrepreneurialism. One of the culminating tasks in the course is to deliver an “investor’s pitch” similar to CBC’s Dragon’s Den. At HSC, this is called “Trojan Trials” and it is helmed by Mr. Nick Timms, the Subject Coordinator of the Arts and Design department along with the assistance of the Alumni office. HSC Alumni, who have been successful in business, are invited back to serve on the panel of mock “investors”; this year’s panel consisted of four entrepreneurs, a couple of whom had pitched on the real Dragon’s Den themselves.

It is no surprise that a course focusing on “entrepreneurial spirit” would excel in the areas of innovation, creativity and entrepreneurialism. So what was I hoping to gain by observing a course that already oozes innovation and creativity? I was looking for three main ideas as I observed the pitches from students:

- Transferable Skills—What did the students need to succeed in a small business or entrepreneurial context? In particular, what essential skills, mindsets and knowledge are needed or were acquired outside the Small Business course. How can we further augment, support and nurture these in other courses?

- Motivation for Excellence—Why did the students want to do well? What motivated them to achieve excellence in their ideation, application, presentation and collaboration? Hint… it isn’t marks… even though this pitch was part of their summative assessment, weighing in at 20% of their final grade… But a mark wasn’t what drove them (at least not entirely)…

- Innovation in Business—I was also looking for a deeper understanding of what innovation looks like in a business context and I wanted a glimpse of the ways Mr. Timms fosters innovation and creativity with his students.

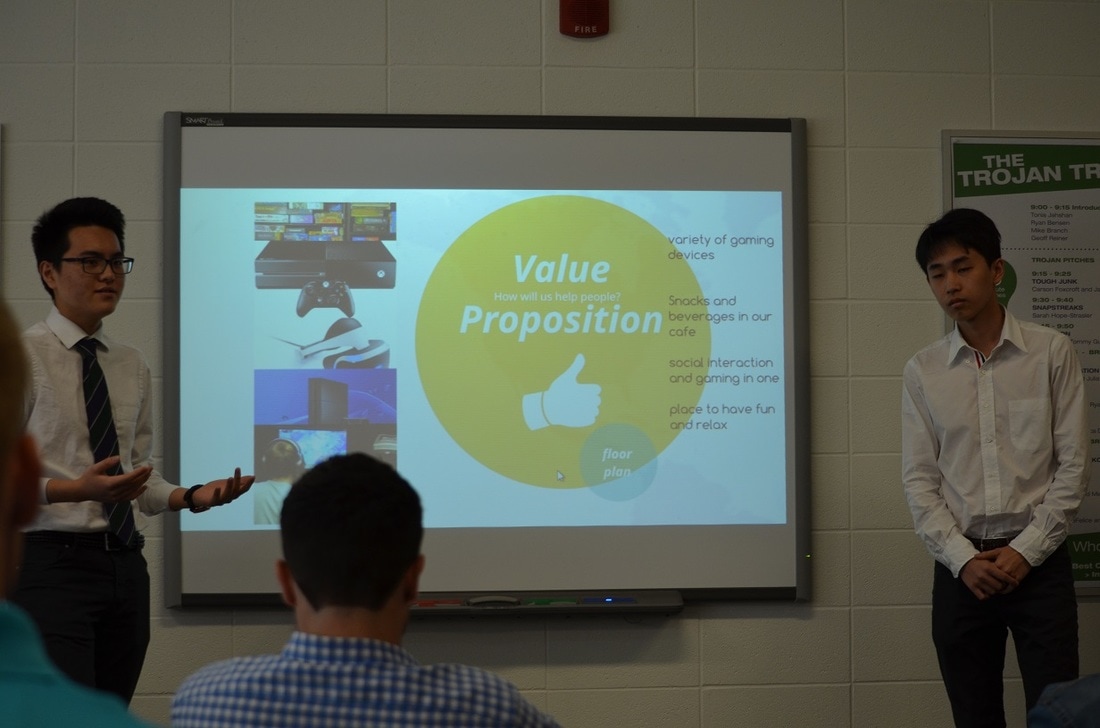

Student entrepreneur Jack Masliwec pitches his business plan along with co-founder Carson Foxcroft.

Student entrepreneur Jack Masliwec pitches his business plan along with co-founder Carson Foxcroft. So, what transferable skills were needed for success? As an English teacher, I couldn’t help but notice the polished, passionate and personal delivery of the pitches; presenters weren’t just going through the motions of an oral presentation… they were communicating. By communicating, I mean they were speaking to a specific audience with the intent of impressing upon them their own personal ideas. Obviously the presenters rehearsed their pitches; however, the feel of the presentations was anything but staged. The students genuinely wanted to persuade their audience (and the panel in particular). The students confidently engaged the attention of their hearers and naturally presented the merits of their ideas to us. Students spoke with their real Voice; it was professional yet personal. There wasn’t a whiff of Wikipedia. Students knew their material inside and out; they were selective and intentional in what they communicated. Their presentations were well paced and their supporting visuals actually supported their presentations (miracle of all miracles…).

Much of our time in school is practice time (and rightly so). However, coaches and stage directors, in particular, know that players and performers don’t give it “their all” until game day or performance night. This assignment turned their presentation into a “game day” performance. As a result, they seemed to give it their all! Another catalyst for excellence was the presence of “creative constraints” (both real and manufactured). The “manufactured constraint” was in the parameters of the assignment itself: the students only had five minutes to pitch and five minutes to answer questions. Time constraints forced the students toward sharp and powerful concision; they had to plan each moment, prepare thoroughly, predict potential problems, practice their performance and valuate every last second of their “stage time.” What really matters? What is most persuasive? What is most memorable? Students were required to hone their presentation and be precise in order to achieve excellence. The real “creative constraints” were the real constraints of business—investment needs, revenue generation, target audience, resources, marketing, feasibility, additional costs, etc. Authenticity garnered a greater demand for excellence. This leads to the next area of observation; that is what about motivation?

Motivation for Excellence. Why did the students seem to stretch themselves and take risks? What motivated them to do well on a school assignment? The most glaring answer is that the Trojan Trials don’t seem like a school assignment. The Trojan Trials has the hallmarks of real-world authenticity. Students had to develop a small business that could actually run; in fact, two of the four groups that I observed had already begun implementing aspects of their business pitches. One group was already making money with their business. In addition, the outside panellists added gravitas to the project; this was not a “please-the-teacher” and “jump-through-hoops” assignment—this was the real deal. The students were being judged by the people that they are seeking to emulate; that is, real entrepreneurs. In addition, the summative presentation pitches are designed with competition in mind; the judges literally judge the students’ ideas and presentation. The panellists are given investment certificates and they get to decide which business gets the “financial backing.” In our current climate of “touchy, feely, everyone wins” it was refreshing and rewarding to see competition serving as cornerstone of challenge. Herein lies the motivator for excellence. I saw students aiming for more than “good enough for the rubric” or “good enough for my report card”—they were aiming to be the best according to real standards of excellence. The competition component required them to be creative in their pitches and presentation, to exceed expectations rather than just meet them. Some of the students wore “team outfits,” had posters, props, demonstrations and handouts. This is risky behaviour. Adolescents risked looking “dorky” with their props, uniforms and their passion for their ideas… They risked looking silly with their grand business schemes. But what adolescents really dislike is being a big “phony” (cp. Holden in Catcher in the Rye). This assignment was anything but phoney; real ideas, real problems, real audience and real competition. Students are risk-takers for things they believe in. In fact, students have always taken “risks” of sorts—they risk not completing homework in order to chat online with friends. They risk doing the bare minimum on a task in order to brag to their pals about how much they achieved with very little effort. They risk doing a lousy job because of lack of preparation or sloth and they risk being apathetic in order to “stay cool” and not be a “nerd.” I have seen many students take “risks” like these. This assignment, however, encouraged real and rewarding risk taking. They owned the idea and they honed the idea; they believed in what they are pitching and they genuinely wanted the audience and the panel to believe too. I never saw Mr. Timms’ rubric, but I am not sure how to grade this sort of student effectiveness and engagement. There are not many “tick boxes” on a rubric that capture authentically what this assignment enables our students to achieve.

Lastly, what did I learn about “Innovation in Business.” Throughout my sabbatical research I have come across a recurring definition of “innovation”—it is something “new” (i.e., an idea that is applied in a new context). Second, an innovation is something executable (i.e., it can be done); and thirdly, it adds value.

In watching an hour of pitches, I saw this threefold definition of innovation serve as the backbone of the students’ entrepreneurialism. Students needed to convince the “investors” that their idea is new, practical and enriching. If the students were weak in any of these areas, the “investors” intuitively offered up suggestions to improve in one of these three aspects of innovation. Is it new? The panel asked questions like, “What makes your idea different than other businesses already in operation?” or “How does your idea fill an open niche in the target market?” The first step of innovating new solutions, then, needs to be problem identification. A business innovation needs to fill an authentic need. Problem identification is achieved through observation, experience, conversation, empathy and experimentation. Many of the pitchers shared the experiences and conversations, the research and the other ways they tested the market and identified the key problem that their business plan seeks to resolve. Or, couched in the language of the classic economics principle of “supply and demand”—what is the “demand” that my business can “supply.”

The ideas were all new, but were they executable? Here the practical business savvy of the panel came into play as well. Questions and suggestions emerged like defining the core business so as to avoid overextension, generating recurring revenue and base income, expansion timeline, crunching the numbers and focusing on target markets that can (and will) pay for services. Lastly, does the idea add value? Here too, the panelists as well as the passionate pitchers made their greatest pleas. Valuation of an idea is perhaps the most essential component in innovation. If it is a good idea, then we can make it work.

The Trojans Trials is a good idea and Mr. Timms et al. have made it work. Kudos to him, his students and collaborators for making real innovation in education!

In watching an hour of pitches, I saw this threefold definition of innovation serve as the backbone of the students’ entrepreneurialism. Students needed to convince the “investors” that their idea is new, practical and enriching. If the students were weak in any of these areas, the “investors” intuitively offered up suggestions to improve in one of these three aspects of innovation. Is it new? The panel asked questions like, “What makes your idea different than other businesses already in operation?” or “How does your idea fill an open niche in the target market?” The first step of innovating new solutions, then, needs to be problem identification. A business innovation needs to fill an authentic need. Problem identification is achieved through observation, experience, conversation, empathy and experimentation. Many of the pitchers shared the experiences and conversations, the research and the other ways they tested the market and identified the key problem that their business plan seeks to resolve. Or, couched in the language of the classic economics principle of “supply and demand”—what is the “demand” that my business can “supply.”

The ideas were all new, but were they executable? Here the practical business savvy of the panel came into play as well. Questions and suggestions emerged like defining the core business so as to avoid overextension, generating recurring revenue and base income, expansion timeline, crunching the numbers and focusing on target markets that can (and will) pay for services. Lastly, does the idea add value? Here too, the panelists as well as the passionate pitchers made their greatest pleas. Valuation of an idea is perhaps the most essential component in innovation. If it is a good idea, then we can make it work.

The Trojans Trials is a good idea and Mr. Timms et al. have made it work. Kudos to him, his students and collaborators for making real innovation in education!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed